“I wish to say a word or two on behalf of the common dog of the country, the unjustly despised Pariah…the true Indian Pariah Dog, mostly red in colour. That we have neglected this animal as a faithful companion, good watchdog, and excellent assistant in many field sports there is no doubt…” – Lieut. General W. Osborn, in the Bombay Natural History Society Journal, 1903

The dingo-type primitive village dogs of Asia and Africa have long been known to science, and to students of dog evolution and of landraces; though they are largely overlooked by general dog breed fans.

The 1960 book ‘Pariahunde’ by Dr Rudolphina Menzel and Dr R Menzel was the first dedicated study of primitive village dogs (those of Israel). The Menzels quote earlier writings on these dogs by zoologists Theophile Studer, Otto Antonius, Emil Hauck, Max Hilzheimer, Theodor Haltenorth, and the painter and author Richard Strebel.

These dogs belong to a broad group classified as primitive and aboriginal dogs, distinct from modern breeds. They include the Australian Dingo, the Canaan Dog of Israel, the New Guinea Singing Dog and the Central African village dog, ancestor of the African Basenji.

The Indian counterpart is the INDog, the original and predominant domestic dog type in the plains and lower-altitude hill ranges of the subcontinent. The type can be described as a landrace.

Our site is dedicated to this pan-Indian aboriginal dog: earlier called the ‘Indian Pariah Dog.’ We prefer to call it the INDog (short for ‘Indian Native Dog’).

The INDog has evolved entirely through natural selection, without deliberate human intervention. The result is a very hardy dog, highly alert, intelligent and capable of independent thinking; very often an owned dog, yet perfectly adapted for survival in a free-ranging life as a human commensal,

The native dog

All Indian languages have a term for ‘native dog,’ clearly acknowledging the existence of an indigenous dog type. Erect ears, short coat and curled tail are widely recognized as characteristics of native dogs.

However a baffling misconception prevails among urban Indians that all local dogs are ‘mongrels’.

While indigenous dog populations have become admixed in cities, the original village dog, the INDog, is in fact less mixed than many modern ‘pure’ European breeds. The majority of European breed dogs have been created only in the last 200 years, often by mixing two or more breeds. In comparison, village dog populations in the more remote parts of India have minimal or no genetic admixture.

Genetic profile

Prior to the recently available tool of genetic testing, we have always used three indicators to determine whether or not the dog population of a particular site is purely indigenous, or admixed with non-native breeds.

The first criterion is uniform INDog-type morphology in the entire free-ranging dog population at the site.

The second is relative geographic remoteness of the site: specifically its distance from large towns and cities.

The third is a ‘traditional’, economically backward human community at the site. The dog populations in such rural communities are generally uniformly INDog-type, since villagers of this socio-economic profile do not acquire European breed dogs.

Urban dog populations, in contrast, have long shown varied morphology including features of common European breeds, indicating significant admixture. These features include completely dropped ear flaps, long-haired coats and shaded sable coats, none of which are seen in INDogs. The presence of large numbers of poorly-supervised pet European breed dogs in cities easily explains the mixed appearance of many urban street dogs. While many individual dogs in towns and cities may still be indigenous, these populations also bear non-native genes which are free to spread.

Our conclusions about purely indigenous populations and admixture were confirmed by the genetic testing of both village and urban Indian dogs between 2009-2015. This was for a landmark study on domestic dog origins in which the INDog Project collaborated: ‘Genetic structure in village dogs reveals a Central Asian domestication origin‘, Shannon and Boyko, 2015, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS). Village dogs in remote rural areas (including in many villages in Odisha state) were found to be indigenous, while urban free-ranging dogs from metro cities showed European ancestry components. Read the paper here.

Geneticists Adam R. Boyko and Ryan H. Boyko discussed the need to preserve indigenous village dog populations in their chapter ‘Dog conservation and the population genetic structure of dogs‘, in the book ‘Free-ranging dogs and wildlife conservation’, edited by Matthew Gompper (2014). ‘Village dogs may also perform important sociocultural functions in many societies, and may contain important genetic and behavioural clues for improving our understanding of the evolutionary history of dogs and the process of domestication. Conserving these village dogs will conserve any local adaptations and preserve the selective and demographic history written into their genes.’ They suggest ideas on how to conserve such populations: ‘Merely maintaining the range of genetic lineages found in modern dogs requires identifying distinct village dog populations and genetically distinct breeds and then conserving a large enough representative sample of these populations. This could potentially be done through the formation of “new” internationally recognized breeds of dogs from indigenous village dog populations, as is being done in India with the Indog.’

The Archaeological Record

We know from the archaeological record that domestic dogs have long existed in the subcontinent. However, the antiquity of the INDog specifically will remain a hypothesis, albeit a reasonable one, until ancient domestic dog DNA is analyzed. Going by the archaeological record, it seems a distinct possibility that the INDogs of today are the direct descendants of the primitive-type dogs that lived in human settlements 4500 years ago and earlier. There is moreover no evidence of any countrywide dog extermination event that could have disrupted this line of descent.

The dingo-type or primitive dog type is represented in ancient artistic depictions and notably in the zoological finds in Mohenjo-daro, which included an interesting dog skull. Sewell and Guha commented on the skull’s similarity to ancient dog remains found in other parts of the world, and to Indian village dogs of the present day. “From the measurements given in the Table it is abundantly clear that the Mohenjo-Daro dog comes extremely close to the Anau dog, and that both are very nearly related to, if not actually identical with, the Paleolithic Canis poutiatini, on the one hand, and the present day Canis familiaris var. dingo on the other…It would, therefore, appear to be probable that the Anau and Mohenjo-Daro dogs, on the one hand, and the dingo dog of Australia and the Indian pariah on the other, possessed a common ancestry…” – Colonel R.B. Seymour Sewell and Dr B. S. Guha, ‘Zoological Remains’, Mohenjo-Daro and the Indus Civilization, edited by John Marshall, 1931. (Read more)

Below: Contemporary art work of the Gond tribe of Central India. Like other tribes of the peninsula, the Gond people traditionally used INDogs for hunting. Though hunting is illegal today, INDogs are still kept as livestock guardians, property guardians and companion dogs in Gond villages.

Indian village dogs described in books and film

There are many references to dogs in ancient Indian literature: some of them are listed in our Archaeological record section. Read more….

Much more recently, a few Englishmen and Indians included Indian village dogs in their writings about Indian fauna.

Lieut. General W. Osborn dedicated an article to the Indian village dog, ‘Hunting with native dogs in India‘ published in the Bombay Natural History Society Journal, 1903: ‘of the good qualities of the true Pariah, as I have to call him, I have seen many instances.’

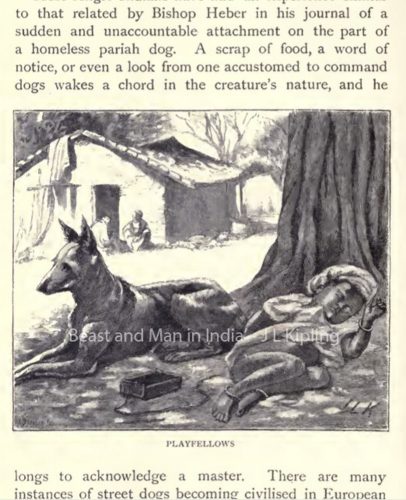

J L Kipling wrote a long and sympathetic description of ownerless village dogs in ‘Beast and Man in India‘ (1891): ‘It should be remembered…that he owes little or nothing to a cruelly indifferent humanity, and that he preserves, as we shall presently see, an innate friendliness which no neglect can quite eradicate.’ He notes that ‘Even the pariah dog enjoys some popular respect as a watch-dog.’

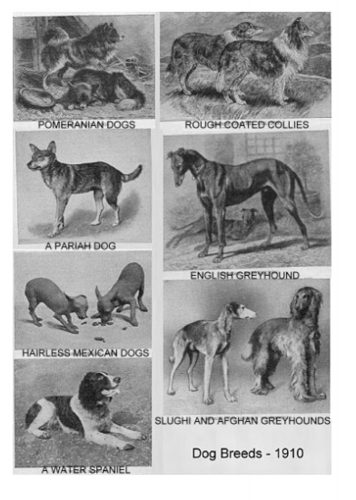

Harmsworth Natural history (1910-11) Volume 10 describes the village dogs of Asia including India, and the marked resemblance of some of them to the Australian Dingo.

The Indian environmentalist M Krishnan was a great dog enthusiast who often wrote about indigenous dog types including the Indian village dog. Here is his beautiful description of the village dog temperament: ‘It is tractable, clever, even sagacious, self-reliant and absolutely incorruptible. It has an extremely hardy constitution and costs next to nothing to feed. There is no better house-dog. It is so clever and willing, you can teach it practically anything, it never makes friends with strangers whatever the bait, and will wake and give voice at the slightest suspicion of anything wrong. It does not keep howling all night, nullifying all attempts at sleep, but barks only when there is good reason. It is this quality, rather than the desire and ability to maul, that is wanted in a watch-dog and the Pariah has it…’ – ‘The Pariah‘, 1944, from the compilation of Krishnan’s writings, ‘Nature’s Spokesman’, edited by Ramachandra Guha (Oxford University Press).

W V Soman in ‘The Indian Dog‘ (Popular Prakashan, India, 1963), the first book on Indian dog breeds, devoted a chapter to the village dog, explaining the difference between the indigenous ‘pariah dog’ and the ‘mongrel,’ or mix-breed. We have uploaded the entire book here for dog enthusiasts.

The Kennel Club of India published an article on INDogs for the first time in their history, in the July 2015 issue of their journal, the Kennel Gazette.

Two recent scientific books feature indigenous village dogs of the world, including INDogs.

‘Dawn of the Dog‘ by the biologist Janice Koler-Matznick (2016) emphasizes the importance of aboriginal dogs in researching domestic dog evolution: ‘Genetics may someday pin down the geographic origin of the dog, but only researching the behaviour of aboriginal dogs and dingoes will give us a clue about why the original dog was able to meld so completely into human society.’ A section of the book is dedicated to accounts of different primitive and aboriginal dogs including the Inuit Dog, New Guinea Dog and the INDog.

The other scientific book is ‘Free-ranging dogs and wildlife conservation‘, edited by Matthew Gompper (2014). INDogs and our efforts to preserve them are mentioned in the chapter ‘Dog conservation and the population genetic structure of dogs‘ by Ryan H. Boyko and Adam R. Boyko.

A National Geographic Channel documentary ‘Search for the First Dog‘ by Working Dog Productions (2003) featured the INDog along with similar primitive dogs of other countries.

The threat of mixture

The biggest threat to INDogs is genetic swamping by non-native breeds. Other indigenous dog populations have succumbed to this, notably in the Americas.

Though at first glance it may appear that there are large populations of purely indigenous village dogs still thriving in the Indian subcontinent, the truth is that non-native dogs are being introduced everywhere through the ‘INDog range.’ In the poorer countries of Asia and Africa it is a common social trend to acquire European breed dogs to display status and spending power.

This phenomenon was largely urban until recently, since urban societies have more disposable income and lifestyle aspirations than rural. Most of the new-rich class of dog owners are not accustomed to dog care, and often leave their pets to roam and breed unsupervised.

Genetic testing of urban and rural Indian dogs showed that urban dogs were mixed with European breeds. ‘Similar patterns in Papua New Guinea (Port Moresby), Nepal (Kathmandu), and India (Mumbai) suggest that foreign dogs are more likely to be brought to (or survive in) urban areas than in more remote regions’- ‘Genetic structure in village dogs reveals a Central Asian domestication origin‘, Shannon and Boyko, 2015.

However, many rural areas now have admixed dog populations as well. The catalyst appears to be increased affluence of the human community. When a rural area gets developed and transformed through such factors as tourism, tea and coffee plantations, or the mushrooming of urban people’s weekend homes, a predictable result is the introduction of European breed dogs and admixture of the indigenous dog population.

Why ‘INDog’?

The name INDog was coined by Col. Gautam Das as an acronym for Indian Native Dog. We wanted an alternative name to the old name ‘Indian Pariah Dog’, which was vague and imprecise in meaning. Moreover the word ‘pariah’ has been long misused and has negative social connotations.

We have a very strong reason for avoiding an Indian language name: there is NO pan-Indian word meaning ‘native’. India has 22 official languages and many more mother tongues. The Hindi word for ‘native’, desi, is used in North India only. ‘Native dog’ translates very differently in other parts of India, for instance, into deshi kukur in Bengali, deshiya naayi in Kannada, deshi kuttra or gavthi kuttra in Marathi, dhekura kukur in Assamese, to list just a few. An English name avoided the whole problem of regional bias.

The INDog Project

Over the last two decades village dogs have received growing scientific attention due to their genetic diversity, behaviour, and their importance in unraveling the mystery of domestic dog evolution. Besides being the subject of genetics and ethology studies, they are also the focus of the Primitive and Aboriginal Dogs Society (PADS), a group of scientists, breed fanciers and enthusiasts that promotes village dog races around the world.

However, within India our indigenous village dogs have never attracted consistent interest or research until recently. Public attitudes to native dogs are clouded by ignorance and fallacies. INDogs are also heavily burdened by the ecology of free-ranging dogs per se. While the entities ‘INDog’ and ‘free-ranging dog’ overlap, the two are not synonymous or interchangeable (in fact, most free-ranging dogs today appear to be mix-breeds). Amid controversies over free-ranging dogs as threats or victims, the identity of the INDog as a unique landrace gets completely ignored.

Our project focuses on this aspect.

We set up the INDog Project to bridge the glaring gap between academia and the dog-literate segment of the general public. It is an independent research and education initiative, not affiliated to any for-profit or non-profit organization.

We first began the project in 2002 under the name ‘Indian Pariah Dog Club’ later renamed ‘INDog Club’. Our blog ‘Are you a primitive dog fan?’ was launched in 2007, and the first version of this website in 2010.

The content of this website has been written and compiled by us. The photos were taken by INDog Project members and associates, along with a few more that have been used with the permission of the owners.

We participated in the research for the genetic diversity study ‘Genetic structure in village dogs reveals a Central Asian domestication origin’, Shannon and Boyko, 2015, published in PNAS.

We maintain an INDog site record, listing locations where pure INDog-type populations are still found.

Our social media community, The INDog Club, disseminates knowledge in an informal manner for general dog lovers. We encourage the adoption of village INDogs. We showcase pet INDogs and INDog-mixes (we call the latter ‘Indies’) on our platforms. Our blog has showcased more than 400 pets in the last ten years. Unlike the ‘man-made’ Indian breeds, the INDog has never undergone selection for any specific function such as hunting or guarding. It has no inherited traits that make it unsuited to being an urban family pet, provided it gets sufficient outdoor exercise. Read our Breed description.

To help first-time owners, we compiled a Temperament Guide based on direct feedback from 45 owners in the INDog Club community.

The Kennel Club of India has expressed interest in INDogs, and support for the INDog Project and our future efforts to standardize and register the breed.

We hope our updated website will enthuse and educate more dog lovers about our indigenous village dogs, and inspire dog fanciers to support our efforts to preserve this unique part of our animal heritage.

Caveat: On urban street dogs

Our project is aimed at dog fanciers and the dog-literate segment of the general public. However, since we started this project in 2002, we have noticed that our material gets used by a number of street dog activists (on both sides of the street dog issue), commercial organisations, rescue organisations and other groups, to promote their own activities and agendas.

With a few exceptions, this has always been done without our knowledge or consent.

Please note that the objectives of this Project are

1. to gain recognition for the specific landrace village dog that we call the INDog, and

2. to share information about this topic with dog lovers.

The genetic profile and history of INDogs have no bearing on the management of street dog populations.

We do not approve the use of our material to justify perpetuating free-ranging dog populations on city streets, highways and other dangerous locations.

Dogs in India evolved to live in small villages and settlements, not in environments densely packed with humans and motorized traffic.

Urban free-ranging dogs live extremely hazardous lives, always vulnerable to injury and death through vehicle hits, or through abuse and ill-treatment. Crowded city conditions force them into constant conflict with humans. It is in the worst interests of both dogs and humans to perpetuate such populations. Safety and welfare should be the only focus here, not ancestry.

We endorse the strategy of high-reach vaccination and neutering programmes by credible, efficient organisations such as the Worldwide Veterinary Service.

Thank you…

Janice Koler-Matznick, founder of Primitive & Aboriginal Dogs Society (PADS), and to Gautam Das who first championed the INDog (and coined the name), for their encouragement, support, and contribution to this Project from its inception.

All the aboriginal breed experts and enthusiasts who have generously contributed text and pictures for this website.

Chlorophyll brand and communications consultancy for creating our logo, all our printed communication material, and for always assisting us even at the shortest notice.

Kiran Khalap for always supporting and promoting The INDog Project in every possible way; for his guidance, feedback and his invaluable contribution to the documentation of INDogs.

Dr Krishna Mohan for generously contributing hours, weeks and months of effort to the execution of this website, despite his demanding professional schedule.

And to the many INDogs and INDog-mixes who inspired us: Kutta my childhood friend; the amiable Janathan Pujary; Peter and Shakha, whom I will never forget; Sharoo, Rani, Tommy, Mala, Camel, Omega Puppy, Toby-Raja; Soupy the diva; Raja and Motu; Wally, Boy and Girl; Smylla, Vanilla and Ivory; Bandu of Moharli; Tibbu of Labangi; Bhura of Karmaziri; Pintoo the goat guardian; Aditya Panda’s beautiful Robin who was the model for our logo; and my own beloved dogs past and present, Lalee, Bandra, Puppy, Kimaya Littlestar, and Kiba.

~ R.K. ~

Anyone seeking to use our content, for educational purposes only, may contact me for permission on rajashree.khalap@gmail.com