This record compiles some of the evidence for the presence of domestic dogs in India since ancient times (at least 5000-6000 years before present).

There are three sections here:

- Ancient dog remains,

- Depictions of dogs in ancient rock art, and

- References to dogs in classical Indian literature.

Please note that we have listed only a few out of the multitude of canine remains, artistic depictions and literary references that have actually been documented. The aim is to give the reader a general idea rather than an exhaustive list of the rich archaeological and historical evidence available on this subject. In the case of dog remains, no doubt many more will be excavated in the future as more and more ancient sites are discovered and explored.

All information on dog remains has been provided by the Archaeozoology Laboratory, Department of Archaeology, Deccan College. Special thanks to Dr Pramod Joglekar and Professor Vasant Shivram Shinde for all their encouragement, patience and support, without which this compilation would not have been possible.

Read about the Archaeozoology Laboratory here.

Dog Remains

Dog remains have been discovered in a large number of excavated sites, of different periods including the Mesolithic, Harappan, Neolithic, Chalcolithic, Iron Age and Early Historic eras.

Note: We do not know whether all these dogs were INDogs, since no ancient DNA has been analyzed yet. The Mohenjo-Daro skull matches contemporary village dog skulls, and many of the dog figures in rock art seem to represent the dingo/primitive type. Since there has been no mass extermination of free-ranging dogs in most of India, since the reach of modern breeds has been limited, and since the primitive type is known to be an ancient domestic dog type, it is a reasonable assumption that most of these ancient dogs were INDogs, and that the INDogs of today are directly descended from them.

Mesolithic Period

Approximately 8th millennium B.C. – 3rd millennium B.C. Transitional phase between hunting-gathering and food production. Marked by the use of small stone tools. Most animal domestication took place in this period.

| Sites at which dog remains were found | Location in subcontinent | Reference and year of publication |

| Adamgarh | Central India | Nath (1967)

However, the faunal material identified by this author might be of a later date than Mesolithic (according to P.K. Thomas and P.P. Joglekar, 1994). See the section on prehistoric rock art for information on dog paintings from the Mesolithic cultural phase. |

Harappan Period

3rd -2nd millennium B.C. Although there were industrial and trade centres, cattle pastoralism was one of the main occupations in the Harappan sites of Gujarat (Western India)

These are some interesting excerpts from publications about animal remains found in Harappan sites.

- Skull in Mohenjo-Daro: The city of Mohenjo-Daro flourished between 2600-1600 BC. A dog skull was described among the finds in ‘Mohenjo-Daro and the Indus Civilization, edited by John Marshall, 1931. The authors of the “Zoological Remains” chapter, Colonel R.B. Seymour Sewell and Dr B. S. Guha, commented on the skull’s similarity to other ancient dog remains found at Anau and Russia (Canis poutiatini), and to Indian village dogs of the present day: “It seems certain that the remains are those of one of the domestic or semi-domestic dogs that are so common at the present day around every Indian village, and at the present time live around the site of the excavations….

“From the measurements given in the Table it is abundantly clear that the Mohenjo-Daro dog comes extremely close to the Anau dog, and that both are very nearly related to, if not actually identical with, the Paleolithic Canis poutiatini, on the one hand, and the present day Canis familiaris var. dingo on the other…It would, therefore, appear to be probable that the Anau and Mohenjo-Daro dogs, on the one hand, and the dingo dog of Australia and the Indian pariah on the other, possessed a common ancestry that can be traced back to the Paleolithic Canis poutiatini of Russia.”

- “Dog bones have been identified at almost all Harappan sites excepting Bara, Orio Timbo, Khanpur and Valabhi…it may be inferred that these bones became mixed with kitchen refuse as a result of the activities of scavengers and predators.” P. K. Thomas and P.P. Joglekar, Holocene Faunal Studies in India, 1994, Department of Archaeology, Deccan College.

- “A few dog bones were found in the collection…These bones got mixed with the kitchen refuse probably because of the scavenging and predatory activities prevalent at the site. Dogs were known to be watch animals guarding the settlements and the domestic stock and also their role in the hunting pursuit of man cannot be ruled out.” P.K. Thomas, Yoshiyuki Matsushima & Arati Deshpande, “Faunal Remains” in Kuntasi, a Harappan Emporium on West Coast, 1996.

- “Other domestic animals included in the assemblage that were used neither for food nor as draft animals were dogs (Canis familiaris) and cats (Felis catus). These animals were relatively rare representing 0.28% (5 fragments) each of the assemblage. No human activity was noticed on these fragments and these were probably kept as pets like today.” P. P.Joglekar and Pankaj Goyal, Faunal Remains from Jaidak (Pithad), a Sorath Harappan Site in Gujarat, 2010.

| Some sites at which dog remains were found | Location in subcontinent | Reference and year of publication |

| Mohenjo-Daro | Pakistan | Sewell and Guha 1931

|

| Harappa | Pakistan | Prasad 1936, Meadow 1991 |

| Kalibangan | North-west India | Nath 1969, Sahu 1988 |

| Rupar | North-west India | Nath 1968, Sharma, Y.D 1989 |

| Alamgirpur | North India | Nath and Biswas 1969, Sahu 1988, P. Joglekar (unpublished report) |

| Rangpur | Western India | Nath 1962-63 |

| Lothal | Western India | Nath and Sreenivasa Rao 1985 |

| Kuntasi | Western India | P.K. Thomas,

Y. Matsushima, A. Deshpande 1996 |

| Surkotada | Western India | Sharma A.K. 1979, 1990 |

| Nageshwar | Western India | Shah and Bhan 1992 |

| Rojdi | Western India | Kane 1989 |

| Malvan | Western India | Alur 1990 |

| Babarkot | Western India | Ryan in press |

| Shikarpur | Western India | Thomas et al in press |

| Padri | Western India | Joglekar c, in press |

| Vagad | Western India | Misra 1988 |

| Zekhada | Western India | Misra 1988 |

| Pabumath | Western India | Misra 1988 |

| Jaidak | Western India | PP Joglekar et al, 2010 |

| Farmana | North India | P.P. Joglekar and C.V. Sharada |

Chalcolithic Period

2nd millennium B.C. Non-urban, non-Harappan cultures, marked by the use of copper and stone tools. Plant and animal husbandry supplemented by hunting.

An excerpt from Holocene Faunal Studies in India, P.K. Thomas and P.P. Joglekar, Man and Environment XIX (1-2) – 1994, Deccan College, Pune: “The dog, man’s companion since very early times, has been reported from a number of Chalcolithic sites. The dog was not a part of the diet of the Harappans. There is, however, a single example for the consumption of dog meat in the Late Jorwe period at Inamgaon, where dog bones have been found charred and with cut marks (Thomas 1984a; 1988; 1989). Ethnographic parallels are also available from the Katodi tribe in the same region who in times of scarcity kill and consume domestic dogs (Thomas 1988).”

| Some sites at which dog remains were found | Location in subcontinent | Reference and year of publication |

| Nevasa | Western India | Clason 1979, Eapen 1960 |

| Daimabad | Western India | Badam 1986 |

| Inamgaon | South-western India | a – Clason 1979; b – Badam 1977; c – Thomas 1988; d – Pawankar & Thomas in press |

| Kaothe | Western India | Thomas & Joglekar 1990 |

| Walki | Western India | Joglekar 1991 |

| Tripuri | Central India | Srivastava 1955 |

| Ahar | North-western India | Shah 1969 |

| Jokha | Western India | Shah 1971 |

| Tuljapur Garhi | Central India | Thomas 1992 |

Neolithic Period

3rd – 2nd millennium B.C. The economy combined agriculture, cattle pastoralism and hunting. A large number of bone tools have been found in the Southern Neolithic cultural phase.

| Some sites at which dog remains were found | Location in subcontinent | Reference and year of publication |

| Burzahom | North India | Nath 1969 |

| Gufkral | North India | Sharma 1979-80, 80-81 |

| Chirand | Eastern India | Nath & Biswas 1980 |

| Brahmagiri | South India | Nath 1963a |

| Kodekal | South India | a – Shah 1973, b – Clason 1979 |

| Palavoy | South India | Reddy 1978-79 |

| Veerapuram | South India | Thomas 1984b |

Early Historic (North and Eastern India)

Late 1st millennium B.C. The economy was based on agriculture and rearing of cattle, sheep and goats. Hunting was possibly no longer a major economic activity but an occasional leisure activity.

| Some sites at which dog remains were found | Location in subcontinent | Reference and year of publication |

| Manjhi | Eastern India | Thomas personal communication |

| Rupar | North India | Hastinapur Period (1100-500 BC) – Nath 1968 |

| Bhagawanpura | North India | Joshi 1978 |

| Atranjikhera | North India | Shah 1983 |

| Rajghat | Eastern India | Narain & Agarawala 1978 |

| Rajghat Period I NBP (600 – 4 century BC) | Eastern India | Narain & Agarawala 1978 |

| Rajghat Period III (0 – 3 century AD) | Eastern India | Narain & Agarawala 1978 |

Iron Age and Early Historic Sites (Central and Western India)

Late 1st millennium B.C. Economy combined cattle pastoralism, farming, hunting, occasionally fishing.

About dog remains at Mahurjhari: “Some of the bones show complete charring and are with cut marks. It is quite possible that dog meat was consumed as is done by certain present-day communities like the Nagas in the north east. Evidence for use of dog meat as food is available from the Late Jorwe levels at Inamgaon (Thomas 1988).”

“Presence of dog and cat bones suggests their close association with the site inhabitants as that of pets, guard dogs or as scavengers.” Excerpt from Faunal Remains from the Iron Age and Early Historical Settlement at Mahurjhari, District Nagpur, Maharashtra, Arati Deshpande-Mukherjee, P.K. Thomas and R.K. Mohanty, Man and Environment XXXV (I), 2010. Department of Archaeology, Deccan College, Pune.

| Some sites at which dog remains were found | Location in subcontinent | Reference and year of publication |

| Kaundinyapura | Central India | Shah 1968 |

| Bhokardan 300-100 BC | Western India | Rao 1974 |

| Nevasa | Western India | Eapen 1960 |

| Devnimori | Western India | Shah 1966 |

| Nagara | Western India | c, 6-5th century BC Shah 1968

d, 4-3rd century BC e, Early Christian Era |

| Jokha | Western India | Shah 1971 |

| Dhatva | Western India | Shah 1975 |

| Mahurjhari | Central India | A. Deshpande et al, 2010 |

Early Historic Sites (South India)

| Some sites at which dog remains were found | Reference and year of publication |

| Yelleshwaram | Alur 1979b |

| Nagarjunakonda | Nath 1963b |

| Peddabankur | 1990 |

Late Historic Sites

| Site at which dog remains were found | Location in subcontinent | Reference and year of publication |

| Balupur | Eastern India | PP Joglekar, unpublished report |

Painted Grey Ware culture (1st millennium B.C.)

| Some sites at which dog remains were found | Location in subcontinent | Reference and year of publication |

| Alamgirpur | North India | PP Joglekar, unpublished report |

| Abhaipur | North India | PP Joglekar, unpublished report |

All the charts in this section are based on Holocene Faunal Studies in India, P.K. Thomas and P.P. Joglekar, Man and Environment XIX (1-2) – 1994, and on other reports of the Archaeozoology Laboratory, Department of Archaeology, Deccan College, Pune.

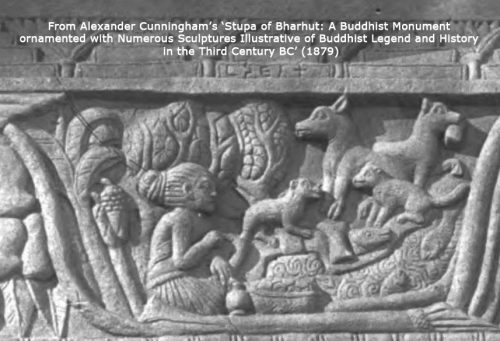

Some depictions of dogs in ancient art

Domestic dogs are depicted in several rock painting sites.

In his detailed study Prehistoric Rock Paintings of Bhimbetka (Abhinav Publications, New Delhi, 1984) Yashodhar Mathpal lists 41 drawings of dogs in the famous Bhimbetka rock shelters in Central India.

“The dog, earliest of the domesticated animals, is recorded in 21 shelters and seven phases. Forty-one recorded drawings are painted in eight colours…”

According to Dr Mathpal’s chronology, 14 of these drawings are from the Mesolithic/prehistoric period; 8 from the transitional phase between the prehistoric and historic periods: and 19 from the historic period.

Another study that mentions dog drawings is Prehistoric Indian Rock Paintings by Erwin Neumayer (OUP 1983).

Some of the drawings mentioned by Neumayer

- A Chalcolithic era painting of a hunting scene in Kharwai, in which a hunter takes aim at an animal which a dog has attacked from the rear.

- In Ramchaja, a man with a dog, Chalcolithic era.

- In Bhimbetka, a Historic period painting of warriors on a campaign that includes a man walking a dog on a leash. The dog has a curled tail and erect ears.

Neumayer mentions that beginning from the Chalcolithic period, paintings depict the individual hunter and his dog who encounter animals and are always victorious. This is a marked change from the group hunting scenes depicted in earlier periods.

Dog drawings are also listed in the paper Tentative Identification and Ecological Status of the Animals depicted in Rock Art of the Upper Chambal Valley – G.L. Badam and S. Prakash, Journal of the Rock Art Society of India (RASI), Vol. 3, Number 1-2, 1992.

The authors mention:

- In Period II, Mesolithic period – dog Canis familiaris; however it may be a depiction of a wolf.

- In Period III, Meso-Chalcolithic – a dog Canis familiaris, drop-eared;

- In Period IV, Chalcolithic – Canis familiaris;

- In Period V, Historic Period – Canis familiaris, drop-eared.

Dr Yashodhar Mathpal mentions several drawings of dogs with hunters and soldiers in Rock Paintings of Bhonrawali Hill in Central India: Documentation and Study (Purakala, Journal of the Rock Art Society of India RASI, Vol. 9, 1998).

One example is Shelter No. 11 B-33, which has a painting of a dog with army men.

Some references to dogs in literature

Although this archaeological record is about dogs in prehistoric times, a few references to dogs in classical Indian literature are worth mentioning. For those interested, Professor Willem Bollee’s scholarly compilation Gone to the Dogs in Ancient India (Beck, 2006, Munchen) is possibly the best source of information on this topic.

Words for “dog” included vakra valadhi, vakra puccha and vakra pucchika, meaning curly-tailed (Monier-Williams Sanskrit-English Dictionary).

Some references:

Rg Veda (composed between 1300 – 1000 BC): Volume 10, verse 8 recounts the story of the celestial dog Sarama who was sent by the gods to find cattle stolen by the Panis, followers of a demon.

Sarama was called devashuni (bitch of the gods). In Hindu mythology she was the mother of all dogs, and her children were called the Sarameyas.

Two of the Sarameyas, Shyama and Shabala, were companions of the god Yama and guarded the road the dead must pass on the way to the hereafter. They are described as chaturaksh or four-eyed.

Volume 10.14.10 of the Rg Veda says “pass by a secure path beyond the two spotted four-eyed dogs, the progeny of Sarama…

Entrust him, O king, to your two dogs, which are your protectors, Yama, the four-eyed guardians of the road, renowned by men.”

Atharva Veda xi 2, 30 connects the god Rudra with dogs.

Mahabharata – (probably composed from about 400 BC onwards, though the story originated several centuries earlier). India’s great epic begins and ends with dog stories.

In the Adi Parva, Sarama appears to curse Janamejaya for his cruel treatment of her son.

In the famous story at the end of the epic, a dog joins the Pandava princes on their journey to heaven. When King Yudhistir finally reaches heaven, he is refused entry unless he leaves the dog outside. He chooses to give up heaven rather than abandon his faithful companion. The dog then reveals himself as the god Dharma, who took this form to test Yudhistir’s moral character.

Panchatantra – (originally composed around the 3rd c BC, but written in its present form several centuries later).

Book I, “The Loss of Friends” refers to the curl in a dog’s tail that can’t be straightened by any means.

“All salve-and sweating-treatments fail

To take the kink from doggy’s tail.”

Translation by Arthur W Ryder, 1925

Book IV of the Panchatantra, “The Loss of Gains,” also contains the story “The Dog who went Abroad.”

Jataka tales (composed around 3rd c BC). The story “The Guilty Dogs,” tells of a king’s unjust massacre of free-roaming dogs for a crime his own palace dogs had committed. The dogs are saved by the intervention of a Bodhisatta who has been born as one of them.

Compiled/written by Rajashree Khalap