Primitive dog: An early type of domestic dog. The primitive dogs of today preserve the appearance of early domestic dogs. They are defined by a specific type (‘primitive type’), as well as by their presumed antiquity. Though they are domestic, they evolved through natural selection, with no intentional human intervention in the selection process.

Primitive type: A generalised appearance with no extreme features: medium height and build, wedge-shaped head with pointed muzzle, erect pointed ears, and a curved tail. This basic appearance is seen in primitive dogs across continents, with regional variations. It characterizes the Australian Dingo, and is sometimes called the ‘dingo type.’

Primitive dogs can be either ‘true primitive dogs’ living in the niche of a wild predator (e.g., Australian Dingo and New Guinea Singing Dog), or ‘primitive village dogs’ that live in human settlements (e.g., INDog, Canaan Dog, Bali Dog).

Primitive breed: A breed that has been developed through intentional selection, from a population of primitive dogs. Examples are the African Basenji and Canaan Dog.

Village dog: Dogs that live free-breeding and partially or entirely free-ranging existences as human commensals and mutualists in many parts of the world. ‘They tend to show a genetic signature of their place of origin and tend not to be closely related to major European dog breeds, although in some places (e.g., Central Namibia and much of the Western Hemisphere) they show significant admixture with European-derived dogs.’ (Boyko et al., 2009 ; Castroviejo-Fisher et al., 2011; Ryan H. Boyko and Adam R. Boyko ‘Dog conservation and the population genetic structure of dogs’ from ‘Free-ranging dogs and wildlife conservation,’ 2013, edited by Matthew E. Gompper)

Following the classification of Ryan H. Boyko and Adam R. Boyko, there are two categories of village dogs: indigenous and admixed.

Indigenous village dog: a village dog that has little admixture with non-native dog breeds.

Admixed village dog: a village dog that has significant admixture with non-native (usually European) dog breeds.

Landrace dog: A landrace is a naturally occurring, geographic population of dogs that evolved to the same type with little or no intentional human-directed selection. The type developed in response to their local environments (for example, double vs single coats depending on climate). Even when some degree of intentional human selection has been involved, landrace dogs are never ‘pure breeds’ in the modern sense of having a narrow gene pool selected for some purpose. Landrace dogs of India include Himalayan sheepdogs, INDogs, and Pandikona Dogs.

Aboriginal dog: Another term for ‘indigenous village dog’

The following definition is adapted from Primitive and Aboriginal Dogs Society (PADS).

Aboriginal dogs should fit one or more of the following criteria:

- They were present in their area of origin before modern (3000 BC or so) non-native human migration

- They are documented, direct pure descendants of native dogs

- They show few, if any, derived characters (other than hairlessness, drop ears and curled tails, which appear to be ancient mutations. A ‘derived’ characteristic is one not found in any species of wild canid, or in any primitive dog. Examples are merle or dilute colouration, and flattened muzzles.

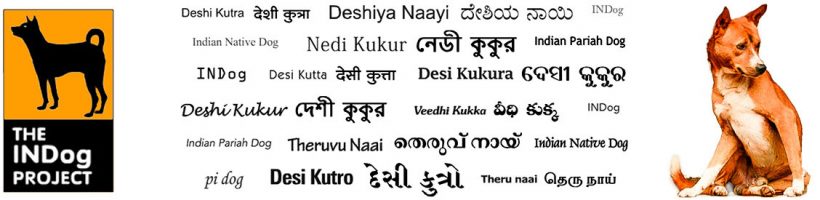

INDog: a name coined by dog expert Gautam Das, and popularised by the INDog Project, to describe the pan-Indian primitive indigenous village dog of the Indian subcontinent. It is the short form of ‘Indian Native Dog.’ INDogs were earlier known as the ‘Indian Pariah Dog.’

Indie dog: Admixed dogs descended from INDogs. This name was introduced and popularised by the INDog Project since 2008. It describes most of the street dogs of India.

Breed: A group of dogs developed to a distinct type, through intentional human selection for desired traits, and by reproductively isolating them from dogs of other breeds

Purebred dog: A dog of only one breed

Pedigree: A recorded line of descent. A pedigreed dog is a purebred dog with such a record.

Admixture: Genetic admixture results from two or more previously isolated populations interbreeding. It introduces new lineages into a population.

Commensalism: A relationship between individuals of two species, in which one species obtains food or other benefits from the other without either harming or benefiting the other.

Mutualism: Association between two or more different species in which each species benefits.

Free-ranging/Free-roaming dog: A dog which lives or roams without restriction or human supervision. In India such dogs may be owned or ownerless (villagers usually allow their pet dogs to roam unsupervised). Ownerless free-roaming dogs are almost always attached to a specific human community and territory, though they may disperse in search of food sources.

Pariah dog: The old term for both ‘primitive dog’ and ‘indigenous village dog.’ The term was used by Europeans to describe the primitive dogs of Asia, from the 19th through the 20th centuries. It was loosely adapted from the name of the Pariah community in Tamil Nadu, although there is no connection whatsoever between this community and these dogs. The term came to be used in an often derogatory sense in the human context, though not in the canine one. However, it is an imprecise and now outdated term for the following reasons:

- It describes both a type and an ecological niche (the primitive type, and the free-ranging scavenger niche), causing confusion

- It has negative social baggage attached to it, especially in parts of India

We promote the use of our name ‘INDog’ and our precise description ‘primitive indigenous village dog,’ rather than the old name ‘Indian Pariah Dog.’

Pi-dog, Pye-dog: other colonial-era names meaning ‘pariah dog’

Mongrel/mutt: A dog of mixed but indeterminate breed, whose lineage is not known. In the past, indigenous village dogs were mistakenly referred to as ‘mongrels.’ We have attempted to clear up this confusion through our communication work.

In peninsular India, most mix-breeds are descended from INDogs, with European breed admixture. We have named them ‘Indies’ or ‘Indie dogs,’ since they all have INDog ancestry. In some regions where native Indian pure breeds have been developed (such as Mudhol Hounds or Rajapalayams), the mix-breeds are usually mixtures of these local breeds and INDogs. In the Himalayas, mix-breeds are descended from the local sheepdogs and European breeds.

Community dog, neighbourhood dog: Terms used by the World Health Organization and World Society for the Protection of Animals in their Guidelines for Dog Population Management, 1990, to describe free-ranging dogs living in a specific area

Stray dog: a dog of any type or breed, roaming without supervision. More precise terms for ‘stray’ are ‘free-ranging,’ ‘free-roaming,’ or ‘free-living.’ For such dogs living in cities, a more precise term is ‘street dog.‘ These terms do not refer to a dog’s breed or type. Purebred dogs abandoned by their owners, become ‘strays’ or street dogs. Street dogs or ‘strays’ adopted into homes become pet dogs. If your pet dog was a former street dog, s/he should no longer be described as a ‘stray.’

In fact, the use of the word ‘stray’ for India’s free-roaming dogs is debatable. Dog enthusiast Gautam Das once pointed out that the usage arose from the British meaning of a dog that is owned by someone and has ‘strayed’ from its home or owner. In Indian languages such as Marathi, the word used is ‘bhatakta’ which more correctly translates as ‘wandering’ or ‘roaming.’ This is rather different from ‘straying’ which always implies that the dog is somewhere it shouldn’t be (with the further implication that a dog should always be in a human dwelling.)

In the Indian context, ownerless dogs are still attached to a territory. When wandering around their home range they are not ‘straying’ from anywhere in a literal sense.

In the countries of northern Europe, the category of free-living or community dog does not exist, and any dog roaming unsupervised would therefore be an abandoned or straying pet. This is an example of English canine terminology being mechanically accepted for usage without taking the Indian context into consideration.

Even pet dogs in villages are usually described as ‘strays’ by urban people, since they wear no collars and roam unsupervised.

It would be best to use the terms ‘street dog,’ or ‘neighbourhood dog’ in the urban context, and ‘free-roaming dog’ or ‘village dog’ in the rural one.

(Note: In the 1990 Guidelines for Dog Population Management, by the World Health Organization and World Society for the Protection of Animals, the term ‘stray’ is described as ‘imprecise because a dog found straying may be lost, abandoned or merely roaming.’)

Feral: The true meaning of feral is a domestic animal that has ‘returned to the wild.’

However, the World Health Organization and World Society for the Protection of Animals (WSPA) use the term ‘feral dog’ in a different sense in their 1990 ‘Guidelines for Dog Population Management’. Their definition of the term is ‘independent, unrestricted. Although it may need human wastes for sustenance, nobody will take responsibility for it.’

In our opinion, the use of the word ‘feral’ for India’s free-ranging dogs is misleading, since these dogs do not live in a wild state in any sense of the term, but are indirectly dependent on humans for survival.

‘Returned to the wild’ applies perfectly to the Australian Dingo, which lives by hunting and eating carrion, with no dependence on humans. Unlike dingoes, dogs described as feral in India are almost always human commensals and scavengers. They are only to be found near human communities, though many of them may not be owned. In fact, even owned dogs in rural areas scavenge.

Predation on wildlife by free-ranging dogs probably reinforces the description of dogs as ‘feral’. However, hunting is unlikely to be the sole source of food for any dogs in India. They are more probably scavenging dogs or even owned village dogs that hunt opportunistically, and are actually dependent on humans for survival. It would be interesting to know whether there are any truly feral dogs in this country.

Compiled/written by Rajashree Khalap