by Dr. Michael W. Fox

Chief Veterinary Consultant

India Project for Animals and Nature

Over 25 years ago I went to the Nilgiris or Blue Mountains, part of the Western Ghats in Tamil Nadu, South India, to do field research on Cuon alpinus, the dhole or Asiatic wild dog. Rudyard Kipling called this jungle and forest dwelling pack hunter the “red peril”.

I never got as close as Mowgli, and it took me twenty years to get back to the area that UNESCO, in recognition of its unique biological and cultural diversity, has recently designated a precious Global Biosphere Reserve. It urgently needs what the late David Brower, founder of the Sierra Club, called CPR- conservation, protection and restoration. The surrounding jungle, forest and shollas (open hills) are rich in flora and fauna, including the endangered Guar (Indian bison), tiger, leopard, Sloth bear, Nilgiri Langur monkey, Malabar squirrel, as well as the largest remaining wild elephant population on the Indian subcontinent.

The whole ecosystem- a fragmented patchwork of state managed, but heavily exploited, wildlife preserves, reserve forests, villages, tribal settlements, plantations (tea, coffee, spices and eucalyptus) is but a few heartbeats away from collapse and mass extinction of indigenous species and peoples.

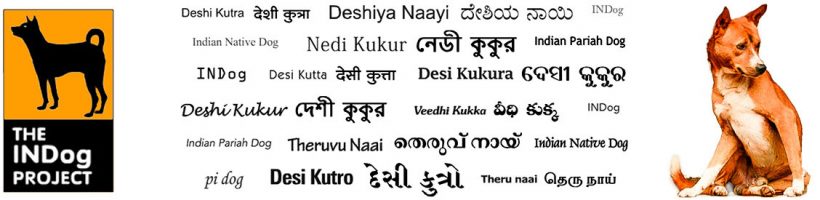

This is where the red dogs come in as part of the problem and part of the solution. I don’t mean Kipling’s red peril dholes (or Chennai as they are called in Tamil). I am referring to the local, still predominantly red “country dog”, a landrace or natural, indigenous, aboriginal dog whom some call the “pariah” dog.

The earth is red, the wild dogs are red and so are the most stunning of these natural dogs who are in every village and tribal settlement. Though some have folded ears like a terrier, most have upright ears and a conformation not unlike the Australian dingo. But they are smaller (25-50 lb), males being more muscular and thicker jawed than the females. Most have short, “tropical” coats, though there are color variations, in part probably due to introduced European pure-breeds and crosses that rich locals keep as much for status as to guard their property. Two or three local dogs from the village would do a far better job as protectors than most of these pure-breeds, but unfortunately many people look down on the “pariah” as being inferior- perhaps a sad legacy of British colonialism.

So while we encourage the spaying and neutering of these latter dogs, we also promote the adoption of our “rehabilitated” (properly fed, socialized, wormed and vaccinated) pups from aboriginal dogs. We advise all to keep the purebreed dogs and their often aboriginal dog-crossed offspring out of the region.

Such advocacy is not breedist or anti-breedist, or some purist ideal. On the contrary, it is to stop the terrible suffering that we see in the Alsatians, Dobermans, Cocker spaniels, Labradors and their progeny. They suffer terribly because they are genetically unsuited for the life and environment of the red dog.

This is evident in their inability to thrive on the subsistence diet of local dogs, whose places they are now taking. They come to IPAN with rickets and overwhelming infections and infestations because their immune systems are so impaired by malnutrition. This is in part because they are rarely able to scavenge and find food for themselves since, unlike most of the indigenous dogs, they are more often house and yard-confined.

These purebreds also strike me as lacking the instinctual “native” intelligence of the local dogs, especially when it comes to fighting off wild boars and leopards, and looking out for heavy traffic and elephants, and avoiding snakes. Most purebreed dogs we see in the region do not have the same innate fear and alarm, and their inquisitiveness, playfulness and naïve hunting behavior gets them into trouble more often with snakes and other wildlife.

Leopards enjoy eating dogs, but the aboriginal dogs are very wary and instinctively stay indoors at night, where they are always alert to the slightest noise.

With the free-running pack of over 40 aboriginal dogs in the compound at IPAN’s Refuge, and the many local dogs whom we have treated for a host of conditions, I have been fortunate to come to know their various ways, and appreciate their different temperaments and personalities. Most show extreme wariness toward anything or anyone unfamiliar. They learn quickly and have incredible memories. Living with two of these dogs in Washington D.C. has been quite an education, especially seeing them relate to various purebreds. Interestingly, they have a greater affinity with American “mutts” (most from the local pound) and the occasional “natural” dog like the one from Dubai and another from Thailand.

Our dogs have different barks for different occasions- visitors at the gate, wild boars outside the fence at night, a monkey in a tree. They often dig up and eat dirt, a source of trace minerals. Those in the villages sometimes form packs and hunt down spotted deer, which we discourage, since they are often used for such illegal poaching.

In the unique environment of our Refuge where, unlike the usual village environment, the dogs do not have to compete for food and all are neutered and spayed, aspects of their behavior and personalities surface that give me a deeper appreciation for the “red dog” of the Nilgiris. The smallest of our males, Dean, is the pack leader. Charisma and not simply size and strength evidently determines who will be “top” dog. Dean had a hard start in life, being semi-starved and left untreated for mange and worms for months. We rescued him from a defunct animal shelter in time to nurse him through distemper. There is “Mani”, another red dog who came to us with a shattered pelvis. He is the “caretaker” of the pack, checking the dogs over for ticks and grooming them with tender care. “Bingo”, a classic red dog, is one of the brightest and best. We amputated one of his front legs after he was brought in mauled by a wild boar while out in the jungle with his owner, who gave him up to us.

Of course not all aboriginal dogs are red-rufus or sandy colored. Colors range from black to white and piebald to brindle. “Xylo”, one brindle female, who starved but somehow survived on the street for the first 5 months of her life (and now lives with me in the US) was the “auntie” to all new pups brought to the refuge, gently licking them and encouraging them to play. “Shadow” is an unusually large white village dog who dragged himself to the Refuge gate after having his back broken by a vehicle over a mile away in the village of Mavanhalla. He had never been to the Refuge before yet knew where to come for help- like the water buffalo who came one day and stood by our gate and waited to be treated for a horrendous maggot (screw worm) infestation..

India Project for Animals and Nature is a division of Global Communications for Conservation Inc. All donations are tax-deductible. Every cent goes to help the animals. Please make donations out to GCC/IPAN and mail to Global Communications for Conservation Inc., 150 East 58th St., 25th Floor, New York, NY 10155.